Free-to-Play and the Death of the Consumer Surplus

“Consumer Surplus” is a term I learned when I studied microeconomics. It’s the consumer’s version of “profit”. It refers to the additional value that a consumer gets from a transaction, beyond the money that they spend. That additional value – value that a theoretically-ideal consumer[1] would have happily paid more money to receive – is said to be “left on the table”, from the perspective of the seller.

There are well-known and widely-practiced techniques for capturing consumer surplus. Discounts, sales and rebates allow you to get at least some money from consumers who otherwise wouldn’t buy your product at full price. Deluxe editions and expansion packs are a way to get additional money from people willing to pay a little extra.

These are reasonably “fair”. As a consumer, you at least retain your freedom of choice – do you take the time and effort to get a discount? Do you pay more and get extras? Either way you’re likely to retain a nice chunk of your consumer surplus.

But what happens if we take this too far…

I’m a game developer, so allow me to talk about games. Specifically about so-called “free-to-play” games.

I won’t talk about how most F2P games are like Skinner boxes. It is all too obvious – and despicable – that many of these games are carefully tuned to be addictive and exploitative in much the same way gambling is.

Let’s talk about the economics of why F2P games exist: to capture as close to 100% of the consumer surplus as possible.

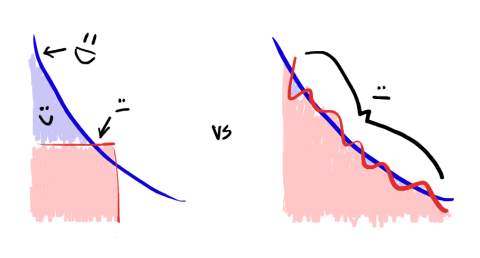

Normally, when pricing a product, you are limited to just a few price points. And, aside from the few consumers willing to pay exactly those amounts, there will always be consumers getting extra value beyond what they paid for.

But free-to-play games have achieved the holy-grail of product pricing: infinitely granular price discrimination. This is where you can charge each and every customer the exact maximum amount they are willing to pay.

If you look at just the demand curve in the above graph, you have the “whales” on the far-left, funnelling in truly absurd amounts of money. And on the right you have a long-tail of users – who probably aren’t paying a thing – but who will occasionally click on an advertisement by accident.

With careful tuning, you can capture every last bit of the consumer surplus, and turn it into profit for yourself. Yay! Money, money, money! An economist’s wet dream!

BUT

I am not an economist. And gamers are not theoretically-ideal consumers.

What do you think is in that consumer surplus?

Joy.

Love of your product. The feeling of ownership. The appreciation a player feels towards you, because you have given them value beyond what they initially paid for.

It’s the simple pleasure a player receives from not having to shove 99 cents of in-app-purchase into a game every time they want to enjoy a dollar’s worth of fun.

(Now seems like a good time to mention that my game, Stick Ninjas, will not be a “free-to-play” game.)

In a market saturated with free-to-play games, a gamer faces the painful dilemma that each game is either going to be terrible, or is going to extract as much money from them as possible.

A gamer no longer has the happy possibility of finding a super-compelling game and having it be a personal entertainment windfall. Instead that gamer becomes a windfall for the developer.

Furthermore, gamers understand, or at least intuit, that developers are incentivised to price games as close to the demand curve as possible. This is a very fine line to tread, and nobody is perfect (much to the chagrin of economists). The slightest error in purchasing judgement on the gamer’s part – or pricing mistake or manipulation on the developer’s part – and any remaining sliver of consumer surplus gets wiped out. The gamer gets ripped off.

It is unsurprising that savvy gamers want to see the free-to-play model go and die in a fire. They hate it, and rightly so.

Contrast this with models that gamers love.

The pay-what-you-want model – most notably implemented by the Humble Bundle – is almost the exact opposite. It allows the consumer to choose how much surplus they want to retain, while opening up the long-tail for developers to make a profit in.

The ever-popular Steam sales similarly allow more consumers to have more consumer surplus, while allowing developers to make more money at the same time.

Even a tiered pricing model – like the one implemented by Introversion for Prison Architect, based on Kickstarter – is welcomed by players. Even though its purpose is to capture some of the consumer surplus up at the left side of the graph – getting more money from enthusiastic players, it still leaves plenty of value left over for players to enjoy. And it’s wholly optional.

~

A lot could probably be said about Apple’s role in all of this (their App Store being Ground Zero of the F2P explosion): The ranking system that has forced the base price down to zero, the technical mechanisms that encourage this kind of pricing model, the lack of features to support other models (e.g.: upgrade pricing, sales, bundles, etc) and the DRM-enforced monopoly Apple holds that prevents others from implementing those features.

And a lot really should be said about Microsoft’s foolish endeavour to drag their platform down the same path with Windows 8 (Casey Muratori makes a good start).

One could also explore how this technically-enabled infinite-price-discrimination is creeping beyond gaming into other areas and making consumers miserable (or turning them to piracy).

But this essay is getting long enough, so I’ll leave those topics for another day. (Although I welcome any insights you’d like to share in the comments.)

If you’d like to continue with another article in a similar vein, “How to Defeat Kolrami” by (be warned) Steve Pavlina is worth reading.

~

[1]: It’s a microeconomics thing. Analogously, if this were a discussion about physics, our ideal consumer would be a point-mass operating in a frictionless vacuum.

Bonus Material: Here’s what absorbing all of the consumer surplus (and then some) looks like.

~

Bonus Material 2 – a numeric explanation of the demand curve and consumer surplus:

Take consumer N. In this example he is willing to pay, at most, $8 for your game. Consumer N-1 will pay more; consumer N+1 will pay less. Put them all in a line and you get the demand curve.

Because you are selling software, each additional copy costs you $0 to produce (allowing us to skip the supply curve). So let’s say you set a fixed price of $5.

Consumer N buys your software for $5 and enjoys his $8 worth of fun. You have made a profit of $5, and N has a consumer surplus of $3. You both come out ahead.

Now you make a free-to-play game. Through cunning metrics and design, you manage to charge N a total of $8 throughout his time with the game. You make $8 profit. N has a consumer surplus of $0.

N still gets his $8 worth of fun. But now he hates your guts.

Comments

Layoric

Great post!

You’ve nailed the reason why I grow to love some games when I revisit them. I recently went back and played Fallout 3 again, after already I got it on special on Steam, and I’m finding I’m enjoying the game more this time around. The consumer surplus I’m getting leaves me with a positive look on the game (even though it crashes quite frequently).

This effect of consumer surplus (or lack of it) would also help explain why I’ve loved games like Team Fortress 2 but grown to dislike them with the introductions of hats. When I originally bought the game as a part of the Orange Box, it was such amazing value and I absolutely loved the game. The introduction of buying hats for real money was not a value add (in my opinion), but just a way to fill the Joy part of your graph.

I think Steam will end up with more of a ‘walled garden’ than they have now, but hopefully Microsoft’s experience with Windows 8 should reinforce what they probably already know, that path doesn’t lead to happy customers or developers. I’ll be interested to see how far they take the ‘Console PC box’ idea though. Thanks again.

Lyw

But now he hates your guts.

Yeah, that’s the point!

Apoorva Joshi

Great article. I’d also like to hear your thoughts on Microsoft killing XNA.

Joha

I’m afraid I just cannot agree with your article. You make blatant assumptions about free-to-play and compare the worst of f2p to the best of pay up front.

If we were still in the pay up front world, the large majority of current and future non-core gamers would still never have found the joy of gaming.

Free to play is here to stay and serves and is just another tool for certain types of games to provide best value for their audience, just like pay up front and other models best fit other cases.

Andrew Russell

@Joha: I think my method of analysis is still valid – and even fits your own conclusion:

F2P opens up the long-tail of potential gamers (the, as you say, “non-core gamers”). The long-tail has a very low position on the demand curve – but a price of “free” is always lower. A F2P game allows a developer to profit from these non-core gamers.

Providing said developer does not perfectly hit (or exceed) the demand curve, then this transaction can also be profitable for these non-core gamers. This is a good thing. Although it cannot be understated that developers have an incentive to hit the demand curve – to the detriment of players – even though as a practical matter this may be impossible.

You are quite right in pointing out that my analysis does not cover more complicated effects like – for example – F2P acting as a kind of “gateway” into other forms of gaming.

But, finally, I must say that the main thrust of my article is to provide an explanation, and legitimacy, for the complaints about F2P from less-casual gamers. These gamers are up at the left-hand side of the graph, and therefore have the most to lose if F2P becomes dominant.

Petr Abdulin

Great post, Andrew!

I’m absolutely avoiding any F2P games. I’ve done that almost intuitively, it’s pretty obvious that such games are usually just money-making machines. But even considering cases where the deal if rather fair — now there is some logic behind why I don’t like them so much.

Cygon

Also in responsive to Joha’s comment, no offense, but I think you’re making even more assumptions of your own.

I don’t see from where you’re taking that the article compares “the best of” paid-up-front games with “the worst of” F2P. I had the impression the these categories of games where compared in general.

I see it this way: an F2P developer has every incentive to make a game that a) keeps players in the game for as long as possible and b) lures them into micro-transactions. A memorable story with a definitive ending, competing on the basis of skill alone, things like that are no longer core business values in F2P.

I also don’t see the basis for your assumption that without F2P, “the large majority of non-core gamers” would never have touched a game (and you seem to be assume that F2P is the only way to reach them.)

The enabler here could very well be the ease of access. As in: visit website, play. Or visit website, download, play. But I don’t see that as an option that’s exclusive to F2P games.

Mechanarchy

Any news, Andrew?